October 2023 – Fungus – Shaggy Inkcap, Coprinus comatus

My wife, Barbara, found this relatively harmless, tall fungus growing inside a partly used open bag of garden compost that had been left inside a greenhouse in our garden. To take this photograph I replanted it in a shady raised border in our courtyard among mostly woodland floor plants to make it easier to photograph in good light. It measures just over 30cm in height above ground.

The shaggy inkcap is a commonly found fungus – with a tall stem and white, tinged with black, shaggy cap providing its name along with others such as ‘lawyer’s wig’ and ‘shaggy mane’. It it normally grows in small groups. It is non-poisonous and is edible when young. Most often the fruiting bodies, or ‘mushrooms’, are all that is visible to us, arising from a subterranean network of tiny filaments called ‘hyphae’. These fruiting bodies produce spores for reproduction, although fungi can also reproduce asexually by fragmentation.

As with all fungus – if in any doubt whatsoever DO NOT EAT IT!

All photos © Copyright Keith Littlejohns

October 2023 – Cyclamen hederifolium alba Found during Tresillian Riverbank Walk

This delightful native cyclamen specimen was found whilst walking along the Tresillian River bridleway between Tresillian and St Clement.

10cm tall, with ivy-shaped leaves marbled with silvery-green patterns. The pure white flowers, with reflexed petals, are borne before or with the leaves which form a carpet of foliage before dying back in the summer. This particular specimen was mostly covered in autumn leaves thus obscuring the emerging leaves.

Please DO NOT remove native wild plants and flowers. It reduces natural native biodiversity, and is illegal anyway!

Photo © Copyright Keith Littlejohns

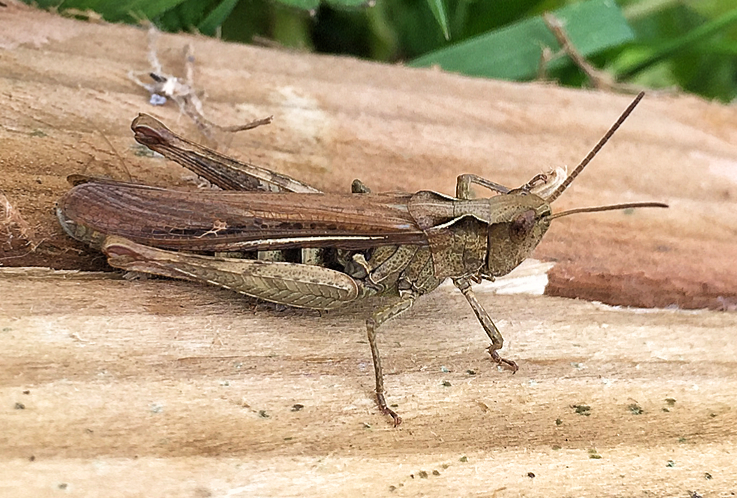

September 2023 – Field Grasshopper found at Tresillian Allotments

This Field grasshopper, Chorthippus brunneus, was found edging its way along a wooden plank at Tresillian Allotments.

Common Field grasshoppers are generally 15-25mm long and brownish, but colour can vary. Short brisk chirps, repeated after a gap, like a pen rubbed down plastic comb. Likes short grass in dry places.

Grasshoppers ‘sing’ for a mate by rubbing a file of pegs on the inside of their back legs against the stiff leading edges of their paper-dry wing-cases. They trill by rubbing a row of pegs on the underside of the top wing, across a raised plectrum on the upperside of the bottom wing.

In the UK, there are 11 native species of grasshopper, including the Common field grasshopper, but around 30 species are known to live and breed here.

Photo © Copyright Keith Littlejohns

August 2023 – Yellow Legged Hornet – Non-Native Species – Please Report Any Sightings

For information only, this is a library photograph.

For information only, this is a library photograph.

Asian hornets, also known as yellow-legged hornets, have been seen in Britain since 2016.

Hornets are the largest members of the wasp family Vespidae and this predatory species could have a devastating impact on British honeybees. The Asian yellow-legged species of hornet is called Vespidae velutina.

Honeybee hunters

The non-native, Asian or yellow-legged hornet, is an invasive species in Britain and their spread could negatively affect our native wildlife already living here.

The issue is that they eat honeybees, they are specialised honeybee predators and beekeepers are concerned.

The hornets raid honeybee hives by sitting outside them and capturing workers as they go in and out. They chop them up and feed the thorax to their young.’

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) is trying to prevent a nationwide Asian hornet invasion, currently through eradication of individuals and nests. But if the species becomes established in the UK, it is likely there is very little that could be done about it.

Asian hornets were first introduced to Europe when they arrived in France in 2004, thought to have been unknowingly transported in cargo. From there they rapidly spread with numerous sightings of the hornets across Western Europe.

These insects have been spotted in several counties across the UK, including in Kent, Cornwall, Dorset, Devon and Hampshire. There have been 45 confirmed sightings in total in the UK since 2016, including 29 nests that have all been destroyed. There has been a sharp increase in sightings in 2023, with at least 22 confirmed reports so far.

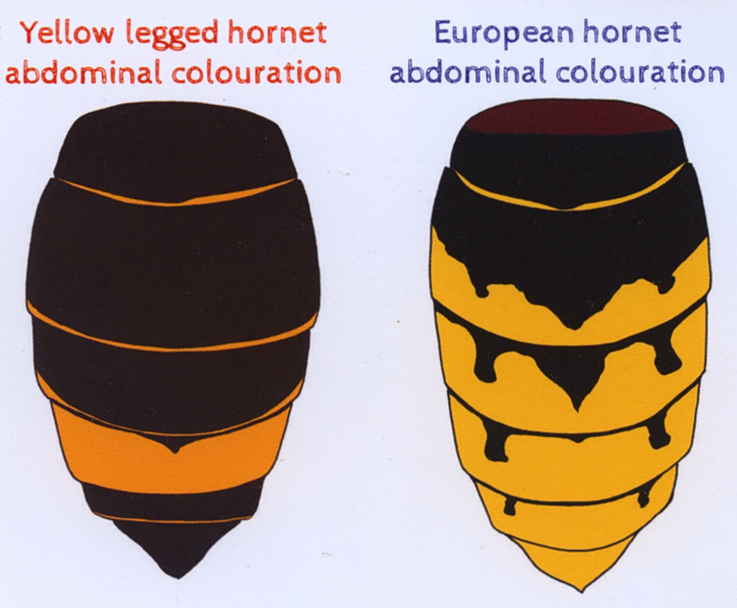

The non-native Asian yellow legged hornet queens reach up to 3 centimetres in length and workers around 2.5 centimetres, and have a dark banded abdominal colouration (as above illustration, left). Whereas, the European hornet is native to Britain and is slightly larger than the invaders. Queens of the European species typically reach 3.5 centimetres long and the workers up to around 3 centimetres, and have a much lighter banded abdominal colouration (as above illustration, right).

The Asian hornet typically builds its nest in the open – they often build on tree branches in the foliage. The nest is patterned, which probably helps to disguise it among the leaves.

Asian hornets are generally active between April and November, with a peak in August and September.

You can report any sightings to the following:

UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH)

There is also a Asian hornet watch app available for iPone/iPad and Android devices.

August/September 2023 – Terrapin Seen in Tresillian River

Fred Taylor sent me these photos he took in the non-tidal part of the Tresillian River near his home. He says that his son and work colleagues saw some at Truro Aldi a few weeks previously.

Terrapins lie somewhere between turtles and tortoises. They happily live in water but also like to bask in the sun. Like turtles, they are omnivores. Unlike them, they don’t have flippers. Instead, they have webbed feet—unlike their land cousins that have feet.

Terrapins originate from the Americas and were initially found on the east coast, from Massachusetts down to Florida and across the Gulf of Mexico up to Texas.

The terrapin population in the UK exploded after the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles craze. Unfortunately, while terrapins start as small as a 50p coin, they grow big and require larger water tanks, more attention, and more food. Many terrapin owners who found it harder than they expected to deal with their pets as they grew, released them into the wild. Despite UK’s occasionally harsh climate, some terrapins do managed to survive, but not exactly thrive.

British weather and climate conditions are not generally conducive to terrapin survival. It is often too cold for terrapins to live happily in the wild as there is not enough sunshine, which is essential for the terrapins to metabolise vitamin D and calcium. When terrapins don’t get enough sunlight, they display softer and more damaged shells. This can happen even to pet terrapins kept indoors, which is why terrapins need a source warmth to survive and thrive in good health.

All photos © Fred Taylor

July/August 2023 – Various Wildlife Sightings in Our Garden in Tresillian

Common Carder Bee – Bombus pascuorum

Colour can be ginger or brown on top of the thorax. This is the only species with black hairs on the abdomen that may make it noticeably blackish or grizzled.

Colour can be ginger or brown on top of the thorax. This is the only species with black hairs on the abdomen that may make it noticeably blackish or grizzled.

Abdomen colour can range from mostly black to almost entirely cream. Old and faded individuals can appear whitish.

Lives in a variety of habitats, including towns and gardens, woodland and arable farmland.

Widespread and common across the UK.

Buff-tailed bumblebee – Bombas terrestris

Buff-tailed bumblebees are the largest of the bumblebees with dark yellow bands at the front of the thorax and middle of the abdomen, queens are the only caste which actually have buff-coloured tails: in workers and males the tails are white, although males in particular often have a narrow but distinct yellow-buff band at the front of the tail.

Buff-tailed bumblebees are the largest of the bumblebees with dark yellow bands at the front of the thorax and middle of the abdomen, queens are the only caste which actually have buff-coloured tails: in workers and males the tails are white, although males in particular often have a narrow but distinct yellow-buff band at the front of the tail.

Nest establishment is in October-November, emerging in early spring, but in recent times workers can be seen flying all winter, feeding particularly on Mahonia bushes as well as other winter flowering plants.They nest underground in large groups of up to 600 bees often using old mammal nests.

Ichneumon wasp Gasteruption jaculator (parasitoid wasp)

ichneumon wasps are quite small, 10–17 millimetres long, beneficial insects that do not have much in common with their stripy namesake.

ichneumon wasps are quite small, 10–17 millimetres long, beneficial insects that do not have much in common with their stripy namesake.

Having the structural appearance of an alien, robotic looking species the head and thorax are completely black. The head is strongly rounded, the thorax is elongated like a long neck (propleura), which separates the head from the body. Its abdomen is strongly stretched, widening at the posterior end and placed on the upper chest (propodeum). The colour of the abdomen is also black, but with distinctive reddish-orange rings. The muscular tibiae of the hind legs are club shaped. The female’s ovipositor is generally very long with a white tip. In resting position, these wasps slowly and rhythmically raise and lower their abdomen.

The females of this parasitic wasp lays her eggs using the long ovipositor on the body of larvae of solitary bees or wasps. On hatching its young larvae will devour such grubs and the supplies of pollen and nectar collected by its victim.

Gasteruption jaculator ichneumon wasps can mostly be encountered from May through September generally feeding on various species of bees and larger wasps.

Crab Spider – Misumena vatia

The crab spider – Misumena vati is so-named because its long front legs resemble those of a crab, and it can also run sideways. Seen between May and August, it is the most common flower spider and the females are larger and seen more frequently than the males. Females are most often encounteres feeding on bumblebees, honeybees, butterflies, moths, hoverflies, whereas males have an active life climbing up and down flowers looking for mates, and eating the occasional insect and piece of pollen to fuel their quest.

The crab spider – Misumena vati is so-named because its long front legs resemble those of a crab, and it can also run sideways. Seen between May and August, it is the most common flower spider and the females are larger and seen more frequently than the males. Females are most often encounteres feeding on bumblebees, honeybees, butterflies, moths, hoverflies, whereas males have an active life climbing up and down flowers looking for mates, and eating the occasional insect and piece of pollen to fuel their quest.

Unlike many spiders, they don’t spin webs to trap insects. Their feeding strategy is a cunning combination of ambush and camouflage. Crab spiders are capable of changing colour to match their chosen flower, providing it is on a spectrum between pale green, yellow, white and pale pink. On a pale flower like yarrow, the spider is well disguised in its natural form, and sometimes have coloured marks on their abdomen and thorax to further camouflage themselves.

These spiders change colour by secreting a liquid yellow pigment into the outer cell layer of the body. On a white base, this pigment is transported into lower layers, so that inner glands, filled with white guanine, become visible. If the spider dwells longer on a white plant, the yellow pigment is often excreted. It will then take the spider much longer to change to yellow, because it will have to produce the yellow pigment first. The colour change is induced by visual feedback; spiders with painted eyes were found to have lost this ability.The colour change from white to yellow takes between 10 and 25 days, the reverse about six days.

The crab spider waits on its chosen flower with its hydraulically powered long front legs wide open, then they clasp shut around the insect and bite them using their fangs, which are specially adapted to pierce and inject their venom. The prey is quickly immobilised, and the spider begins to squirt digestive juices into the body, turning it into a convenient soup, which the spider simply sucks out the contents with straw-like fangs. When alarmed during feeding, they hang on to their prey and rear their front legs up in a warning pose to deter an aggressor.

Male crab spiders have to be very careful not to end up being eaten during their approach for mating, but this is where their small size comes in handy – they simply sneak up and crawl on.

The largest females generally have the most reproductive success, therefore the more prey they can get the better.

The females use their spun silk exclusively to protect their egg sac, and they normally only have just one brood in their entire lifetime. Choosing a leaf tip and folding it over to create a pocket in which the egg sac is laid, then wraps it around with silk guarding it until she dies.

Golden-ringed Dragonfly – Cordulegaster boltonii

The Golden-ringed Dragonfly Cordulegaster boltonii, is a striking dragonfly and the longest British species, the only member of its genus to be found in the United Kingdom. A very large species, males average 74 mm and the larger females 84 mm. Wingspan is up to 101 mm.

The Golden-ringed Dragonfly Cordulegaster boltonii, is a striking dragonfly and the longest British species, the only member of its genus to be found in the United Kingdom. A very large species, males average 74 mm and the larger females 84 mm. Wingspan is up to 101 mm.

The female lays her eggs in shallow water, having a preference for slow running, acidic streams.

The hairy larvae live at the bottom of the water and are well camouflaged amongst the silt. They emerge after about 2–5 years, and usually under the cover of darkness.

They feed mainly on insects ranging from small prey such as midges, flies, butterflies and even bumblebees.

Flight period is from early June through to end August. Golden-ringed Dragonfly are basically a moorland species hence found chiefly in western side of Great Britain

Holly Blue Butterfly – Celastrina argiolus

The Holly Blue butterfly is found throughout much of England and Wales, becoming scarcer further north and absent in Scotland.

The Holly Blue butterfly is found throughout much of England and Wales, becoming scarcer further north and absent in Scotland.

Its numbers fluctuate from year to year in response to the climate and the numbers of the parasitic wasp Listrodomus nycthemerus, which kill many caterpillars.

Although not seen in large numbers these little, blue butterflies are commonly reported from urban gardens, along hedgerows and on the edges of woodland.

In the British Isles there are two generations with the first recorded from March to June and the second from June to October.

Common Toad – Bufo bufo

Photo is of a very young toad that has only recently taken on its full characteristic shape, and is approximately 2cm long.

Photo is of a very young toad that has only recently taken on its full characteristic shape, and is approximately 2cm long.

Common toads are amphibians, breeding in ponds during the spring and spending much of the rest of the year feeding in woodland, gardens, hedgerows and tussocky grassland. They are famous for their mass migrations back to their breeding ponds on the first warm, damp evenings of the year, often around St. Valentine’s Day.

Common toads tend to breed in larger, deeper ponds than common frogs, but still frequent gardens. They hibernate over winter, often under log piles, stones or even in old flower pots!

The common toad has olive-brown, warty skin, copper eyes and short back legs. It walks rather than hops, and lays its spawn in long strings around aquatic plants, with two rows of eggs per string.

Adult toad’s reach a length of 8-13cm, weigh up to 80g, have an average lifespan is up to 4 years and are generally active from February to October.

All toad’s are protected in the UK under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981. Priority Species under the UK Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework.

All Above Photos: © Copyright Keith Littlejohns, and were taken in our garden in Heron Close.

May 8th 2023 – Deer Sighted in Tresillian

A young male Roe Deer, Capreolus capreolus was spotted in the naturalised woodland behind Heron Close. It stayed for only a short time and has not been seen since. The male roe deer is commonly called a ‘roebuck’.

A young male Roe Deer, Capreolus capreolus was spotted in the naturalised woodland behind Heron Close. It stayed for only a short time and has not been seen since. The male roe deer is commonly called a ‘roebuck’.

This is our most common native deer and is widespread across mainland Britain, but less common in Wales and southest Kent. Roe deer are usually solitary in summer, but will congregate in small groups during the winter. They live in and have a preference for areas of mixed countryside that includes woodland, farmland, grassland and heathland. They eat buds and leaves from trees and shrubs that can be reach, as well as ferns, grasses, heathers and other low growing vegetation at ground level.

Unlike their much larger red deer cousins, the roe deer males have rather short antlers up to 20–25 cm (8–10 in) long, with just two or three points. Their antlers begin to grow in November, shedding the velvet from them in the spring. By summer the rutting season has started. Following mating, they will shed their antlers around October time and start the process to grow new ones again.

After mating, females delay implantation of the fertilised egg until January of the following year. This is so that the young are not born during the harshest winter months. Two or three, white-spotted kids are born in May or June.

Being a relatively small deer the average weight is 15–35 kg (35–75 lb). It’s possible for roe deer to live for 20 years, but more commonly 8 to 10 years is the norm.

Photo: Copyright © Keith Littlejohns.